Fashion may remain hooked on a skinny ideal, but Alexandra Shulman’s selfie shows she is moving on

Alexandra Shulman has, everyone says, been terribly brave. Daring, even. Some might say heroic, given the circumstances, which are that the outgoing editor of Vogue magazine is all of 59, and was therefore presumably expected to live out her remaining days hidden beneath dust sheets.

Yet instead this week she posted a bikini selfie online, looking – well, like a 59-year-old on holiday generally does, relaxed, cheery and definitely not 25 any more. The response on Instagram to what many saw as a blow against unrealistic, airbrushed images of women was overwhelmingly positive. “Why was this not our September cover?!” gushed a former magazine colleague. Why indeed?

It’s just a guess, but one answer might be that the magazine’s publishers would never have let that happen. They would surely have worried that young women wouldn’t buy it, would recoil from this beaming Ghost of Summer Future. They would have feared designers responding to a real, older body in their clothes with the same disgust as the late critic AA Gill, who, reviewing Professor Mary Beard’s TV appearances a few years back, suggested that, at 57, she “really should be kept away from cameras”.

There is a grudging place reserved for older women in the public eye who somehow contrive to look freakishly youthful, but those who have aged in recognisably human fashion are still expected to do the decent thing and disappear. No wonder so many women hesitate over the holiday packing, wondering what they can still get away with; a YouGov poll this week found two thirds of over-50s wouldn’t feel confident being seen in public in a bikini, and, more depressingly, nor would half of 18- to 24-year-olds.

And that’s what makes Shulman’s picture if not exactly brave, then subversive. She is refusing to go quietly despite being 59 in an industry where 30 might as well be dead, and where to have actual thighs instead of a puzzling gap where human thighs are generally located is deemed shocking.

And frankly, she looks liberated. After quarter of a century of being asked in practically every interview why she doesn’t look as people expect the editors of glossy magazines to look – namely skeletal and terrifyingly groomed – how glorious it must feel just to pull on a Boden bikini (a label surely too mumsy for Vogue) and not give a stuff. She said, when she left the magazine after 25 years, that she longed to do something different. One wonders now just how big a break with the past she had in mind.

Her close ally at the magazine, Lucinda Chambers, who was fired as fashion director shortly after Shulman quit, certainly hasn’t held back. “Truth be told, I haven’t read Vogue for years,” Chambers declared after she left, adding that the clothes were “just irrelevant for most people – so ridiculously expensive”. But the glossies are kept afloat by high-end designers’ advertising and so their clothes dominate editorial pages, even though few readers can afford them and clothes are barely even the fashion houses’ core business now. The real money is in flogging designer sunglasses, perfumes and handbags to the masses; the point of the ridiculously expensive clothes, at least when draped on the “right” people, is to create iconic images that make millions want to buy a cheaper piece of the magic.

Chambers knew, she wrote, that one cover featuring the cult fashion figure Alexa Chung wearing a “stupid Michael Kors T-shirt” was no good but “he’s a big advertiser so I knew why I had to do it”. Fashion people may see themselves as edgy, but glossies are in some ways more instinctively conformist than the fustiest old broadsheet newspaper.

The really brave thing, of course, would have been to rail against all this while still in a position to make a difference. In fairness to Shulman, she did push the boundaries during her time at Vogue, exposing some of the hidden ways in which big business – and not just the magazines, which generally take the blame – dictates and enforces a restrictive norm of female beauty that viciously erodes women’s confidence.

In 2009, she publicly warned designers that, by making clothes in impossibly small sample sizes, they were driving models to become ridiculously thin. More recently, she criticised designers who refused to lend clothes for a cover shoot featuring a size 16 model, as if their brands would be tainted by association with her. Less forgivably, she has suggested that the paucity of black Vogue cover models simply reflects racism in society rather than in magazine offices, arguing that hers is an industry “where the mass of the consumers are white and where, on the whole, mainstream ideas sell”.

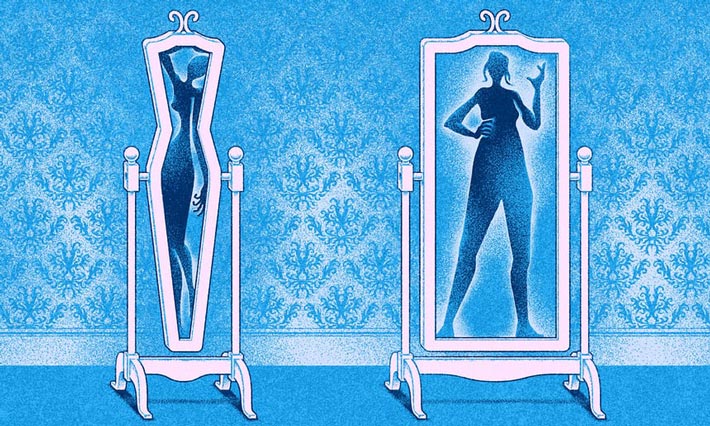

But it reveals much about that industry that even mild deviations from a rigidly policed ideal of beauty – young, skinny, white, impossibly beautiful – are considered commercially risky. Fashion sales essentially rely on convincing us that there is a “right” way for women to look, and that the 99% who don’t resemble the model can get there for the price of the dress she’s wearing. Relax the definition of perfect, accept that more women are fine as they are, and who needs the dress?

The pragmatic reason for using impossibly attractive models, however attractiveness is defined, is meanwhile, as Boden’s eponymous founder Johnnie Boden once put it, that “you can’t hold up a mirror to customers. If you make it too real, it becomes mumsy.” Put a normal woman in a bikini and it’s obvious how little of the magic is down to the clothes, how hard magazines have to work just to make them look interesting. Some bikinis are prettier than others, but it’s just something you wear to go swimming. There’s only so much a few triangles of cloth can achieve.

And it’s Shulman’s life, not her wardrobe, that creates the real interest in her picture. It’s only as real as any Instagram selfie, which means it’s the version of reality she has chosen to share with the world. But this looks very much like a portrait of an older woman confident in herself, not averse to poking vested interests with a stick, embarking on a new stage of life in which the clothes look less interesting than the person inside them. Hurrah, at least, for that.

Source: theguardian.com